Many cry, but few pay to protect China's relics

- By Robert Raymer

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, January 31, 2012

E-mail China.org.cn, January 31, 2012

|

|

|

Robert Raymer |

I read a recent article about the destruction of a famous pair of Chinese architects' Beijing siheyuan courtyard home and reacted predictably, knee-jerkishly, like nine out of 10 Chinese polled that "the… home should not be demolished because it has high historic value."

Then I looked closer and I wondered: Who really cared about home of Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin? There are many issues involved, including why the Beijing Municipal Government issued two demolition notices on the property officially designated a "cultural relic." However, I am interested with what should be preserved when perceived current necessities (e.g., "progress") clashes with the desire to conserve the past (i.e., "China's heritage").

Although most Chinese agree that the old should be preserved, no one did much for the Liang Sicheng house as, over time, it decayed and began to fall down around itself. Too often this happens to structures deemed "historic" - time, after all, is the greatest destructor of history.

Ironically, Liang Sicheng was an early, but unsuccessful, champion of preserving old Beijing, but also the "Father of Modern Chinese Architecture." So why did his children, who took up his profession as today's architects and the Architectural Society of China, not protest as their father's historical home fell into disrepair? Why were they not the "godfathers" contributing to its rescue? Apparently, those very people who we expect would most value the historical value of the architect's house were largely indifferent to its fate, especially if saving it might affect their time and pocketbooks.

|

|

|

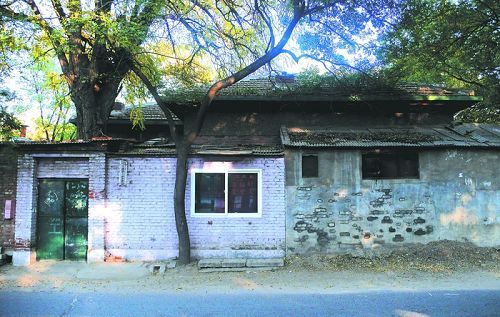

The former courtyard residence of late architect Liang Sicheng and Phyllis Lin |

Every old structure cannot be saved. There would not be enough room for new ones, and the ancient buildings, after all, replaced something even more ancient. To be designated a historic site or cultural relic, a structure or piece of ground should be required to have a financing godfather, whether a private organization, an individual or a government entity from the national to the village level. Certificates of cultural relics would be issued and remain valid only as long as the godfathers continue to lobby for the welfare of the site and fund its conservation, whether donations from NGOs, such as the Beijing Cultural Protection Center, or tax-supported governmental agencies, such as the Ministry of Culture at the national level or a cultural artifacts office at the county level. Certificates of cultural relic would be integral parts of property deeds, spelling out what development was allowed. However, when godfathers lost advocacy and financial interest in these cultural godchildren, the historical sites would no longer be subject to restrictions, if in a reasonable period of time another godfather did not step up to become the relic's sponsor.

I do not know if the Liang Sicheng courtyard house is of architectural significance. Its value seems more related to the fact that the famous architect lived in it. Certainly, other more striking structures in Beijing and throughout China were bulldozed over essentially anonymously. However, citizens and organizations that would preserve China's past need to carefully choose what to advocate for and to put their money where their mouths are to maintain it.

Robert Raymer is a Panama-based former career Foreign Service officer, was U.S. Consul General in Panama City, San Salvador and Buenos Aires and a foreign policy advisor in the administration of Panamanian President Martin Torrijos.

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.