Lifeless satellite falls back to Earth

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail

China Daily, September 24, 2011

E-mail

China Daily, September 24, 2011

Fragments from an old 6-ton NASA satellite hurtled toward Earth on Friday, while the exact site of the crash-landing remained a mystery into the final hours.

![Junk left from colliding satellites floats through space in this computer-generated image. NASA confirmed that two communication satellites from the United States and Russia collided 800 kilometers above northern Siberia on Sept 10. [Provided to China Daily] Lifeless satellite falls back to Earth](http://images.china.cn/attachement/jpg/site1007/20110924/00114320def10fe7866b3b.jpg) |

| Junk left from colliding satellites floats through space in this computer-generated image. NASA confirmed that two communication satellites from the United States and Russia collided 800 kilometers above northern Siberia on Sept 10. [Provided to China Daily] |

The US space agency has stressed that the risk is "extremely small" that any of the 26 chunks that are expected to survive the fiery re-entry into Earth's atmosphere will hit one of the planet's seven billion people a one in 3,200 chance.

"Re-entry is possible sometime during the afternoon or early evening of Sept 23, Eastern Daylight Time," NASA said on its website on Thursday night.

That would be early morning Saturday Beijing time.

"It is still too early to predict the time and location of re-entry with any more certainty, but predictions will become more refined in the next 24 hours."

The influence of solar flares and the tumbling motion of the satellite make narrowing down the landing a particularly difficult task, experts said as the Internet lit up with rumors of where and when it would fall.

The US Department of Defense and NASA were busy tracking the debris and keeping all federal disaster agencies informed, a NASA spokeswoman said.

The Federal Aviation Administration issued a notice on Thursday to pilots and flight crews of the potential hazard and urged them to "report any observed falling space debris to the appropriate (air traffic control) facility and include position, altitude, time and direction of debris observed," CNN said.

The satellite was launched in 1991 and was designed to provide data for better understanding Earth's upper atmosphere and the effects of natural and human interactions on the atmosphere. The satellite was deactivated in 2005 as it ran out of fuel and was left orbiting Earth.

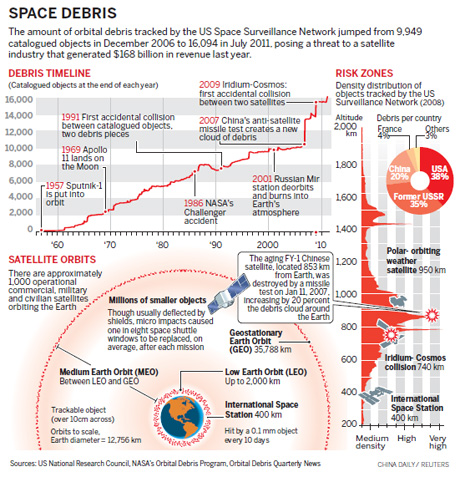

Orbital debris experts say space junk of this size from broken-down satellites and spent rockets tends to fall back to Earth about once a year, though this is the biggest NASA satellite to fall in three decades.

NASA's Skylab crashed into western Australia in 1979.

The surviving chunks of the tour-bus sized satellite will include titanium fuel tanks, beryllium housing and stainless steel batteries and wheel rims. The parts may weigh as little as one kg or as much as 158 kg, NASA said.

Orbital debris scientists say the pieces will fall somewhere between 57 north latitude and 57 south latitude, which covers most of the populated world.

The debris field is expected to span 800 square kilometers.

Pang Zhihao, a researcher from the Chinese Research Institute of Space Technology, told Xinhua that the crash could have been avoided had the satellite been put into a higher orbit, or manipulated to drop in the South Pacific when it had abundant fuel.

Pang said most spacecraft will incinerate upon re-entering Earth's atmosphere, and the debris will mostly likely fall into the ocean or hit an uninhabited area.

NASA has also said that in 50 years of space exploration no one has ever been confirmed injured by falling space junk.

The craft contains no fuel and so is not expected to explode on impact.

"No consideration ever was given to shooting it down," NASA spokeswoman Beth Dickey said.

NASA has warned anyone who comes across what they believe may be debris not to touch it but to contact authorities for assistance.

Space law professor Frans von der Dunk from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln's College of Law told AFP that the United States will likely have to pay damages to any country where the debris falls.

"The damage to be compensated is essentially without limit," von der Dunk said, referring to the 1972 Liability Convention to which the United States is one of 80 signatories.

"Damage here concerns 'loss of life, personal injury or other impairment of health; or loss of or damage to property of States or of persons, natural or juridical, or property of international intergovernmental organizations,'" he said, reading from the agreement.

However, the issue could get thornier if the debris causes damage in a country that is not part of the convention.

"The number of countries so far theoretically at risk is rather large, so there may be an issue if damage would be caused to a state not being party to the Liability Convention," he said.

AFP-Xinhua

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)

Add your comments...

Add your comments...

- User Name Required

- Your Comment

- Racist, abusive and off-topic comments may be removed by the moderator.