Mock Mars mission simulates landing on Red Planet

After 257 days in a locked, windowless steel capsule, researchers on a mock trip to Mars ventured from their cramped quarters in heavy space suits Monday, trudging into a sand-covered room to plant flags on a simulated Red Planet.

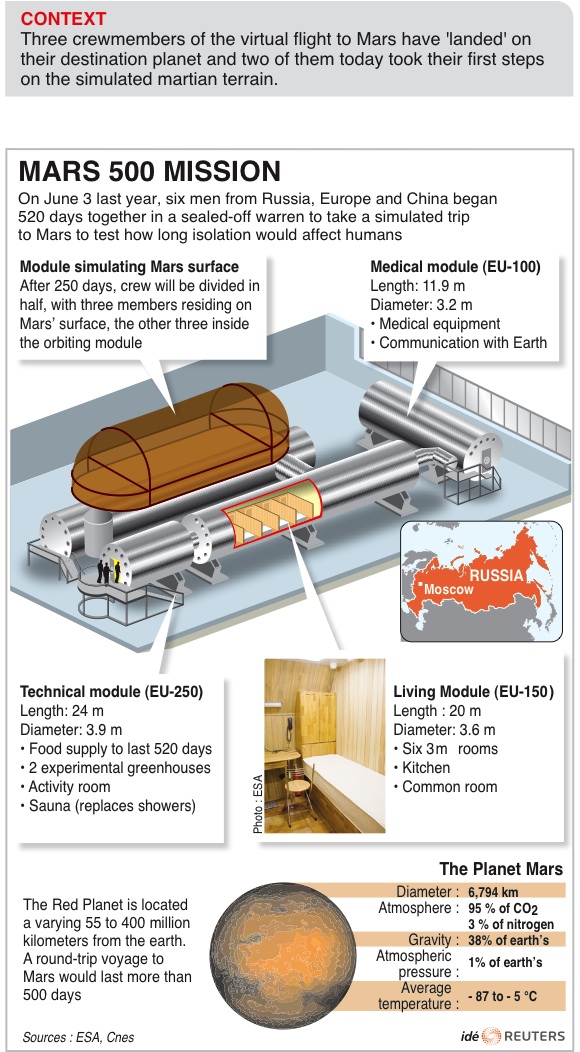

The all-male crew of three Russians, a Frenchman, an Italian-Colombian and a Chinese entered a network of modules at a Moscow space research center last June to imitate the 520-day flight and see how they cope with the constricted, isolating conditions of space travel - minus the weightlessness.

|

|

Technicians watch a feed from the Mars 500 project at mission control in the town of Korolyov on the outskirts of Moscow February 14, 2011. [Photo/Agencies] |

Several participants donned 30-kilogram (66-pound) suits to perform Monday's mock landing in an adjacent capsule. They planted the flags of Russia, China and the European Space Agency, took "samples" from the ground and conducted faux scientific experiments.

"All systems have been working normally. The crew are feeling fine," said Vitaly Davydov, deputy head of the Russian space agency.

Psychologists said long confinement would put the team members under stress as they grow increasingly tired of each other's company. Psychological conditions can even be more challenging on a mock mission than a real flight because the crew won't experience any of the euphoria or dangers of actual space travel.

Davydov described the experiment as an important part of preparation for a flight to Mars and predicted that the real mission could take place in about 20 years, but only with international cooperation.

Martin Zell, a European Space Agency official overseeing the experiment, called the mission a "really strong asset for future undertakings of mankind in space, for its ambition to fly finally to the Red Planet."

The facility in western Moscow includes living compartments the size of a bus connected with several other modules for experiments and exercise. The video footage of the landing was shown on a big screen at Russia's Mission Control Center in Korolyov outside Moscow, which is used to handle manned missions to the international space stations.

The organizers have said the experiment could be disrupted for medical or technical reasons, or if some of the participants demand it be stopped.

So far the crew has been coping. "After a couple of weeks they were really a team, certainly with some temporary ups and downs of individual crewmembers," Zell told The Associated Press.

"A big challenge is missing daylight, missing visual perceptions," he said. "They also have to live with the food which they have on board and with the air which they have on board."

The crew communicates with the organizers and their families via the Internet _ delayed and occasionally disrupted to imitate the effects of space travel. They eat canned food similar to that offered on the International Space Station.

Christer Fuglesang, an ESA astronaut who took part in two shuttle missions and made five real spacewalks, said the 18-month duration of the experiment strongly challenged the participants.

"What they must miss, I'm sure, is the interaction with their families and friends," he told the AP.

The crew comprises Russians Alexey Sitev, 38, Sukhrob Kamolov, 37 and Alexander Smoleyevsky, 33, Frenchman Romain Charles, Italian-Colombian Diego Urbina and Wang Yue from China. The organizers said each crew member will be paid about $97,000.

|

Zell said the crew even made makeshift decorations for Christmas, using equipment components. "They are very creative," he said.

A similar experiment in 1999-2000 at the same Moscow institute went awry when a Canadian woman complained of being forcibly kissed by a Russian team captain. She also said two Russian crew members had a fist fight that left blood splattered on the walls. Russian officials downplayed the incidents, attributing them to cultural gaps and stress.

Ushakov denied Monday that the previously botched experiment prompted organizers to leave women out, saying they will be included into future simulations.

A real flight to Mars is decades away because of huge costs and massive technological challenges, particularly the task of creating a compact shield that will protect the crew from deadly space radiation.

President Barack Obama said last month that he foresaw sending astronauts to orbit Mars by the mid-2030s.

0

0