Brazil's new president – the rhetoric and reality

- By Heiko Khoo and Micheal Roberts

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, November 3, 2018

E-mail China.org.cn, November 3, 2018

Brazil's new President Jair Bolsonaro will form the most right-wing administration among the top 20 nations of the world. Bolsonaro says he wants to crush "communism" and restore "law and order" by putting the military in control of the streets and stuffing the Supreme Court with his appointed judges. He wants to loosen gun control, crack down on crime, support President Trump's policies, and open up the economy and the Amazon forests to "proper exploitation."

Why did Bolsonaro win the election? His main support base is the small business sector, the wealthy, and the burgeoning evangelical religious movement. These groups were virulently opposed to the government of the Workers Party (PT) that held office from 2002 under former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2011) and President Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016). The PT was accused of undermining family values, and of taxing and regulating business to the benefit of low-income families. However, the main rallying cry underpinning Bolsonaro's victory was anger at rising crime, high unemployment and corruption within the traditional "political class."

Among the middle classes, Bolsonaro is widely seen as the man to end corruption, while the PT stands accused of "stealing" from the country. Former President Lula is in custody for corruption, probably on trumped up charges, which ensured he could not run in the election. However, Bolsonaro also won because of widespread disillusionment within the working class at the PT. After the collapse of commodity prices in resources and agriculture, the economy went into recession, and the PT is often blamed for this.

Bolsonaro failed to secure a majority among the 147 million Brazilians entitled to vote. It is compulsory to vote in Brazil, but nearly 30 percent spoilt their ballots or entered blank papers. The PT remains the largest party in the lower house of the Brazilian Congress, in which 30 different parties are represented. So it will not be easy for Bolsonaro to get many of his most reactionary measures agreed.

The Brazilian economy is in trouble and growth is stagnating at best.

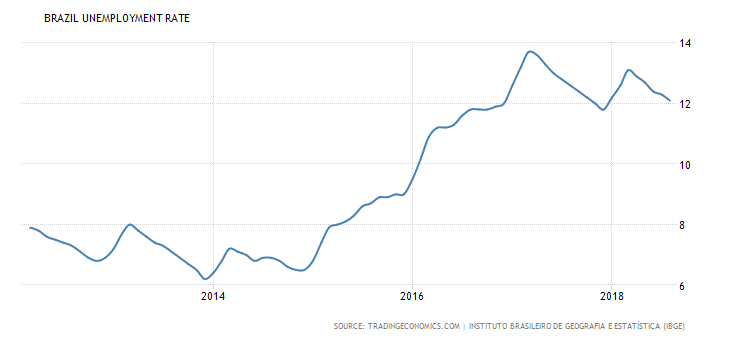

Unemployment is near post-global crash highs.

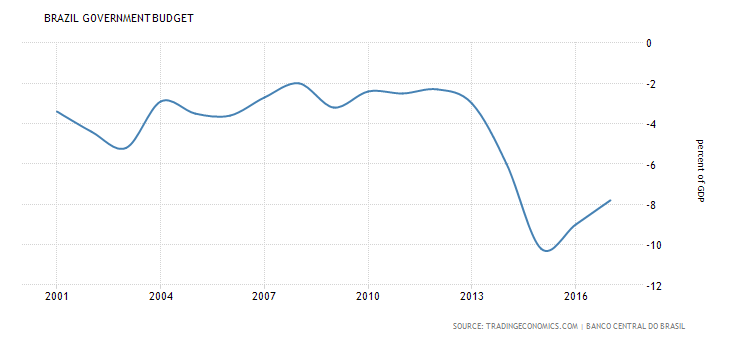

Because the rich do not pay taxes, and inequality of income and wealth is one of the highest in the world, the government does not raise enough revenue to avoid huge annual deficits.

Brazil's public sector runs the largest debt to GDP among all emerging economies.

The solution of the Bolsonaro administration will be austerity, namely, privatization and deregulation of industry and the banks, and further cuts in public spending, above all, the destruction of Brazil's state pension scheme. However, many state governments are already bust or starved of funds.

Stock and bond markets have risen on hopes that Mr. Bolsonaro will deliver on this. These "neo-liberal" policies will be pursued by Bolsonaro's likely finance chief Paulo Guedes. This University of Chicago-trained economist is co-founder of BTG Pactual, once the country's biggest home-grown independent investment bank. Markets expect Guedes to maintain a freeze on fiscal spending introduced by current President Michel Temer. They also see him introducing formal autonomy for the central bank and allowing the state-owned oil company Petrobras to set fuel prices at "market levels."

In the evening of Oct. 28, following the victory of Bolsonaro, Guedes said pension reform as well as slashing the "state's privileges and waste" would be a top government priority. So, just as in the U.S., Brazilians will hear law and order rhetoric from their president, keen to be tough on crime, while introducing strident neo-liberal reforms to help big business by driving down the share of income going to the workers.

International agencies, foreign investors and Brazilian big business all want the administration to impose austerity, labor "flexibility" and privatization. This will drive up inequality, and ironically, it will not reduce public sector debt because economic growth and tax revenues will be too low. Indeed, the IMF forecasts that debt will be much higher by 2020.

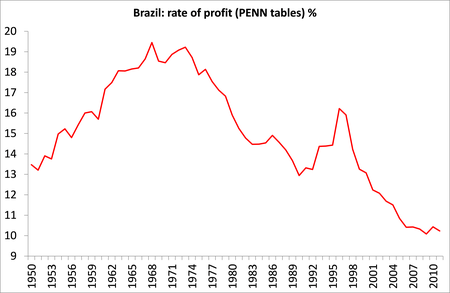

At the same time, more than half of Brazil's population remain below a monthly income per head of R$560. To cut this level of poverty to under 25 percent would require productivity four times as fast as the current rate. There is no prospect of that happening because the profitability of Brazilian capital is too low. The profitability of Brazil's dominant capitalist sector has experienced a long secular decline, imposing continual downward pressure on investment and growth.

It will not be easy for Brazil's ruling elite to slash public spending and wages and attract foreign capital. So, Brazilian capitalism will likely remain stuck in a low growth, low profitability future, characterized by continuing political and economic paralysis.

Heiko Khoo is a columnist with China.org.cn.

For more information please visit:http://china.org.cn/opinion/heikokhoo.htm

Michael Roberts is a London based Marxist economist. He published the "The Great Recession" in 2008 and "Essays on Inequality" in 2014.

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.