?The future of the G2

- By Sumantra Maitra

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, February 2, 2018

E-mail China.org.cn, February 2, 2018

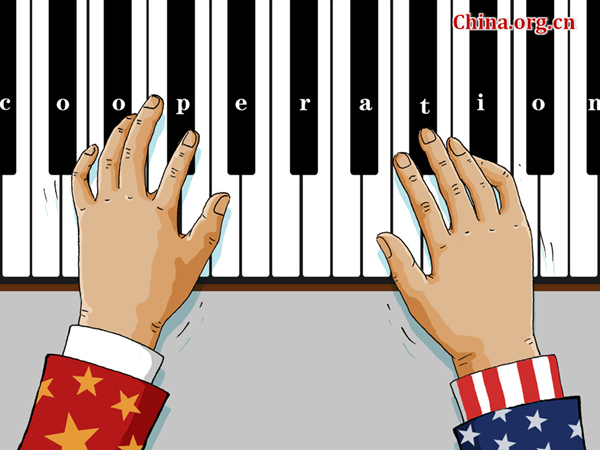

Recently, a couple of discussions revolving around China were prominent in the United Kingdom. One was a lecture delivered at Peking University by the eminent British historian Niall Ferguson. That speech, republished in the Global Times, considered the fate of the Group of Two, or G2, a proposed cooperative alliance between the USA and China. After the financial crisis of 2008, the historian asks, is the G2 viable?

Ferguson answers in the affirmative. In response to American protectionism, he observes, China has demonstrated an alternative vision of international order. This was symbolized when Chinese President Xi Jinping made the case for globalization at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. It is an important acknowledgement from a British historian, and highlights the differences in European thinking about China. Why is the "liberal international order" facing dire trouble?

It is primarily due to economics, not war, Ferguson points out. The 2008 financial collapse showed the model was broken beyond repair, and it resulted in American retrenchment.

With the U.S. in recession, Europe, which was already siding with China on climate change, financial institutions and free trade, started to court China even more vigorously, with France and Britain each vying to be the biggest Chinese partner from the region.

Where does that lead us? Here again, Ferguson wishes to avoid a "Thucydides Trap," which has been a staple of American policy. He states that the "preferable alternative is that China and the U.S. recognize their common interests as great powers facing multiple threats, such as Islamic terrorism, nuclear proliferation, cyber warfare and climate change." But he warns that a partnership between the two countries is not enough; the other great powers must also support the efforts of the G2.

So then, what's stopping the G2? A second piece being discussed in Western foreign policy circles, "U.S.-China Relations and the Liberal World Order,"which was published in January by Chatham House, solves this puzzle. If China is a global institutional power, as evident from the AIIB and other initiatives, will it follow the same foreign policy as the United States over the last few decades? The authors explain that Xi Jinping envisions Chinese policy differently from Western strategies. The key departures are the emphasis on long-term "peaceful development," which pursues the "maintenance of a positive and beneficial relation with the outside world," and not seeking hegemony. Put simply, the Chinese development model, which is described as "win-win" by the Chinese government, is distinct from the "relative gain" strategy in the West, which emphasizes liberal interventionism and hegemony. Chinese policy is thus considerably astute and will remain so, if it avoids imperial overreach.

An understanding of contemporary global politics suggests that there are fundamentally two currents. One is the narrow, nationalist current. This is reflected in American protectionism, as well as certain East and Central European states. The other is liberalism, which is prevalent among both liberals and neoconservatives, and necessitates a global rule of law as a perquisite for any trade.

There is now a glimpse of a third system which, while focusing on trade interests, the global market and competitive advantage, also respects sovereignty and independence. It understands the differences of culture and society, and is not so hubristic as to force regime change in support of trade. This is arguably the current of the future, a trade system which is also based on the mutual respect of sovereignty, and is more realistic and achievable than others. The future of the G2, therefore, remains open.

Sumantra Maitra is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit:

http://www.formacion-profesional-a-distancia.com/opinion/SumantraMaitra.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors only, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.