Abe's new 'mandate'

- By Michael Roberts and Heiko Khoo

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, October 26, 2017

E-mail China.org.cn, October 26, 2017

|

|

|

Japanese Prime Minister and President of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) Shinzo Abe poses while putting a rosette on his name at the LDP headquarters in Tokyo, Japan, on Oct. 22, 2017. [Photo/Xinhua] |

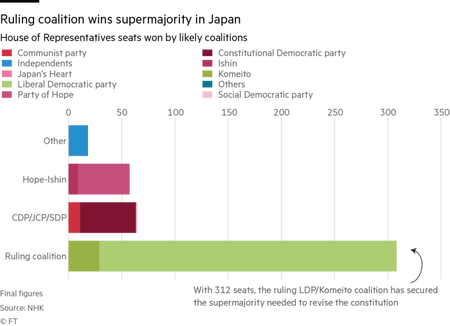

The Japanese stock market rocketed to a 21-year high with a record 15-day winning streak after the result of the Japanese parliamentary election. The Japanese capitalists are pleased that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) won the snap general election and, with its incumbent coalition, the Buddhist-affiliated Komeito Party, retained the two-thirds majority necessary to pass legislation without recourse to the upper house.

Abe will now claim he has a mandate to change Japan's "pacifist" constitution and adopt an offensive militarist and imperialist stance for the first time since 1945. Abe says this is necessary to resist nuclear attack from North Korea and to contain China. In reality, the ruling elite of the LDP is seeking military independence from America.

Abe needs to proceed cautiously because Japanese citizens are sharply divided about such constitutional change. So, he plans to delay this until after 2020.

Sadly, Japan's electorate had little choice. The opposition was in disarray. The Democratic Party offered no alternative economic or political policies and, when the conservative governor of Tokyo, Yuriko Koike, decided to set up her own national party, "The Party of Hope," the Democrats immediately split: half joined Koike and the others formed another party, called the "Constitutional Democratic Party" under Yukio Edano. By opposing constitutional change, this party became the main opposition and the "The Party of Hope" flopped.

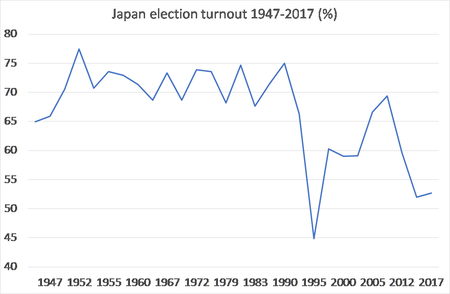

Voter turnout was the second lowest since 1945 at 52 percent, up only 1 percent on 2014. Most of Japan's working class see no party to represent their interests, and so they don't vote. Actually, Abe's LDP gained less seats than in 2014 (down 6) as did Komeito (down 5).

In 2014, Abe also called a snap election. Then he sought a mandate for "Abenomics," which supports monetary easing, fiscal tightening and "supply-side neoliberal reforms" designed to rejuvenate Japan's stagnant economy. How has Japan done since then? The objective of getting Japan out of deflation (falling prices) failed despite the advice of top Keynesians (Paul Krugman) and monetarists (Ben Bernanke) - and a massive injection of money by the Bank of Japan. The inflation rate hovers around zero after three years of effort.

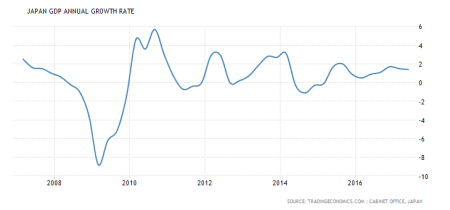

But why strive to "cause" inflation if the economy is growing? Indeed, Japan's real GDP rose for six consecutive quarters and the country experienced modest economic growth after a sharp recession in 2014.

The population fell by over a million in the last decade. Japan is rapidly getting older so real per capita GDP rose even more. Nevertheless, in dollar terms, Japan's GDP has stagnated and the yen fell against other currencies. Dollar GDP is below that in the early 1990s - the falling population only compensated for that.

The second thrust of Abenomics has been fiscal spending. No other G7 government is running such a large budget deficit, Keynesian-style. The annual deficit had reached nearly 10 percent of GDP in 2012, although some recovery in real GDP reduced the deficit to around 4 percent. The Japanese government has run a deficit for over 25 consecutive years, while public sector debt is well over 130 percent of GDP. This Keynesian effort achieved a miserable average annual economic growth of under 1 percent in the last decade. Abe intends to hike sales tax, to reduce the deficit at the expense of working-class consumption. He also hopes to liberalize gaming and allow casinos to suck in revenue at the expense of the desperate.

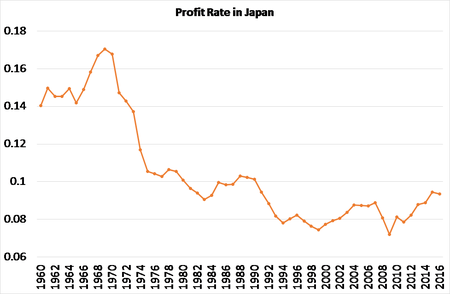

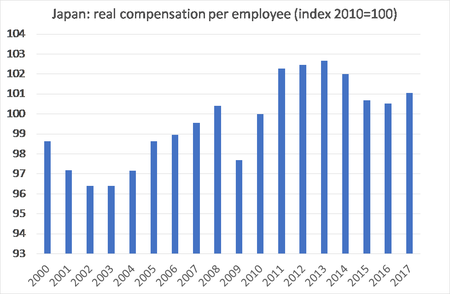

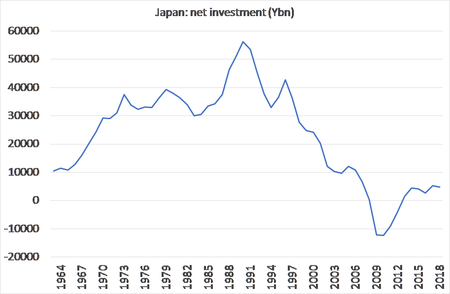

The real purpose of Abenomics is his "supply-side" reforms: designed to reduce labour costs and boost capitalist profitability. So far this has worked. Japan's rate of profit had been in long-term decline from the 1960s. Then, privatization and reduction in labor rights produced a modest recovery in profitability in the early 2000s but it was the global credit boom that fuelled this. "The Great Recession" put a stop to that. Under Abe, per capita real wages were held down and profitability rose. However, so far, Japanese capital has not responded by boosting investment.

Net investment (after depreciation) is very low and gross private investment is anemic. Japanese companies prefer to employ more labor at low wages rather than invest, or they take their investment overseas much like the U.S. and U.K. capitalists.

Industrial production growth accelerated somewhat as a falling yen helped exports pick up as the world economy grew. Business sentiment improved; and Japanese capital is more optimistic. However, the bulk of Japan's people, have not seen an improvement - many are low paid or part-time workers. With low investment, low productivity growth and low profit rates: Japanese capitalism remains frail.

Heiko Khoo is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit:http://china.org.cn/opinion/heikokhoo.htm

Michael Roberts is a London based Marxist economist. He published the "The Great Recession" in 2008 and "Essays on Inequality" in 2014

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn