Top-level international talent recruitment remains challenging

- By Richard de Grijs

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, January 28, 2017

E-mail China.org.cn, January 28, 2017

|

|

|

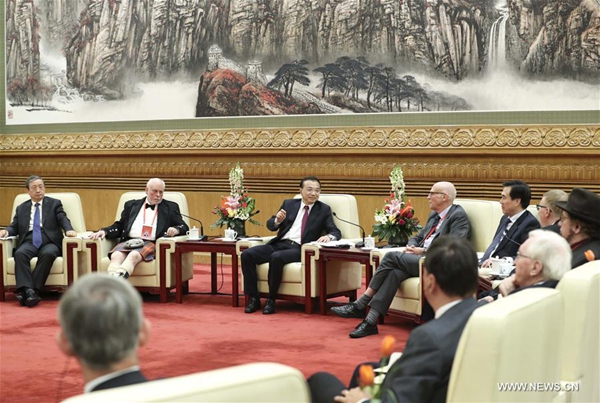

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang meets with foreign experts working in China prior to the Lunar Chinese New Year, in Beijing, capital of China, Jan. 20, 2017. [Xinhua/Pang Xinglei] |

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang's recent announcement was significant. The timing, however, caused it to be somewhat hidden among the international headlines covering Donald Trump's inauguration as the 45th U.S. president. The message, nevertheless, was clear: China welcomes high-level international talent to boost its innovation, business and scientific development.

This follows a period of sustained policy changes aimed at attracting more foreign experts to boost the country's innovation-driven growth and increase its soft power. Judging from reports in the international media, President Xi Jinping's keynote speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos on Jan. 17 represented a well-received push to highlight China's soft power, showing the world that the country welcomes professionals with the right skill sets. Indeed, Premier Li expressed his strong interest to "fully tap into the wisdom and creativity of every individual," from scholar or senior corporate officer.

A number of practical measures have been implemented in recent months to make the country a more attractive destination for high-level foreign talent. These include easing red tape and requirements to obtain work permits and, eventually, permanent residency for Master's and doctorate degree holders.

However, Zhang Jianguo, head of the State Administration of Foreign Experts Affairs, put his finger astutely on one of the most significant impediments preventing the country from becoming a scientific and innovation powerhouse in the short term. He pointed out that the lack of top-tier talent in cutting-edge domains and China's insufficient attraction to high-end talent are hampering sustained progress, according to news reports in the People's Daily.

It will take some time to address these issues comprehensively. A two-pronged approach of attracting high-level foreign expertise and supporting innovative homegrown research teams will likely be most productive in the medium term.

In recent years, we have seen sustained improvements in attracting high-level, mostly junior foreign talent. Indeed, year-on-year the number of newly minted doctorate degree holders from abroad that venture to Chinese research institutions increases. While the number of non-Chinese postdoctoral researchers at mainland universities and research institutions was a mere trickle only a decade ago, China is rapidly becoming a credible destination for recent graduates from prestigious international programs at top universities in Europe and the U.S.A.

Current recruitment challenges can be grouped into three categories. One revolves around the general perception of China as a destination country. With few exceptions, international scientists based in China appear to thrive and they also seem quite happy in their personal lives. When we talk to our friends and colleagues abroad, however, we often face a lack of comprehension in relation to any positive comments we may make about the possibilities of pursuing a research career in China. President Xi's speech in Davos was an important attempt to address such perceptions.

Second, a potential practical impediment facing junior scientists coming to China is that they need to retain high international visibility if they ever want to secure a higher-level job elsewhere in the international community. Junior scientists need to establish themselves first, which is ideally done through networking in their respective international communities, but the mere fact of China's geographical location with respect to the traditional scientific powerhouses may make this a daunting and potentially costly prospect.

Third, Western postdoctoral scientists are often concerned about the perceptions of their mentors in relation to a move to China, where the relative rankings of the host universities comes into play. This latter aspect is, therefore, yet another reason why Chinese universities are hotly pursuing improved rankings in the international league tables - an approach that has yielded fruit in recent years.

Although recruitment of high-level junior international talent to China appears to be on a positive trajectory, the same cannot yet be said of their senior counterparts. The number of long-term senior scientists at China's top universities is still small. This may well change as Chinese research programs and institutes become more competitive internationally, but it is very important to realize that attracting senior foreign talent to long-term appointments will only succeed if they feel at home and respected at their new positions.

This implies that they should be taken seriously as members of their newly adopted Chinese scientific community rather than merely seen as temporary visitors. They should ideally be allowed to be actively involved in policy discussions affecting their fields and be eligible to compete for the nation's top awards and funding sources. Only then will China's research environment be on a par with those of its main competitors on the international stage. And only then will China have a fighting chance to attract the best and brightest international talents to its top research institutes.

Richard de Grijs is a Dutch professor of astrophysics at the Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics (Peking University) in Beijing. He has been actively involved in recruiting international postdoctoral researchers to China since 2009.

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.