Building collapses in China must be avoided

- By Ember Swift

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, April 11, 2014

E-mail China.org.cn, April 11, 2014

|

|

|

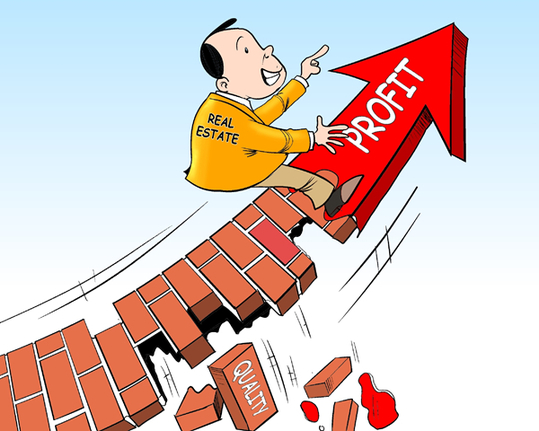

Quality matters [By Jiao Haiyang/China.org.cn] |

The collapse of the building in Ningbo on April 4, 2014 is yet another in a series of building collapses in China over the past several years that has generated plays on words in overseas articles such as the Washington Post's "The Real China Housing Collapse: 'Vintage' Buildings" (published April 9, 2014.)

This issue has been generating worldwide attention, especially since both the tragic Chinese earthquakes in Sichuan (2009) and Yushu (2010) reported that many schools and apartment buildings were more easily toppled by the quakes due to their "shoddy construction." Certainly, this phenomenon is generating much doubt among overseas consumers regarding the reliability and durability of Chinese construction. China needs to be vigilant in solving these issues or else doubts surrounding quality control will quickly translate into the realm of all Chinese-made goods.

What is most definitely lacking in China, as a result of its status as a developing nation with unprecedented urban growth, is a nationwide set of building construction standards and codes that must undergo strict testing and requisite approvals before finished buildings are permitted occupancy. These kinds of systems have a downside: they slow the process of urban growth, which in turn impacts the booming economy. Since developing countries are eager to "catch up," cutting procedural corners is common practice. Unfortunately, the result is more than tragic; it's deadly.

Now China has a plethora of what can only be called "temporary" structures that are increasingly dangerous. Nearing the end of their lifespan, Chinese buildings that were built in the booming 80s and 90s are now threatening to crumble. Cracks in walls or doors that don't shut properly due to twisted frames are examples of early signs.

Like in the building in Ningbo, for example, residents noticed that their windows were buckling, but the inspection office did not insist on evacuation, simply labeling it as a "C Rated" building but not notifying residents or condemning the premises. The local neighborhood committee merely accepted these findings and persisted in believing the building was safe enough for residency. This either points to unskilled inspectors, a misplacement of authority regarding the dissemination of information and final decision making or a municipal apathy that actively avoided engaging in the trouble of relocation.

In these situations, there is always the question of who is to blame. Fiscal compensation is required for both the residents and the building owners. While the burden of responsibility must be placed in someone's hands, the focus on assigning fault is mercenary rather than socialist. The question: "Who should pay?" is often the loudest question, rather than: "How do we avoid this from happening again in the future?" China needs to focus primarily on answering the latter question, before it moves onto the former.