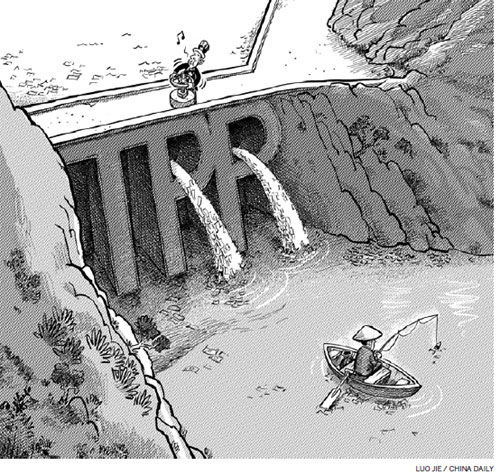

TPP has inherent financing flaws

- By Kevin P. Gallagher

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China Daily, October 9, 2013

E-mail China Daily, October 9, 2013

Many world leaders who gathered for the Asia-Pacific Economic Conference meetings in Bali, Indonesia, had hoped to sign the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement. The pact would have brought together key Pacific Rim countries into a trading bloc that the United States hopes could counter China's growing influence in the region.

But the talks remain stalled. Among the sticking points is the US' insistence on TPP trading partners dismantling regulations for cross-border finance. But many TPP countries will have none of it, and for good reason.

Not only does the US stand on the wrong side of experience and economic theory, it is also pursuing a policy that runs counter to International Monetary Fund guidelines. This is especially noteworthy, because the IMF was considered the handmaiden of the US government in such matters until recent years. Unfortunately, the IMF's newfound independence and insight have not yet rubbed off on the US government.

The surprising development aside, the US could learn a few lessons from the TPP countries when it comes to overseeing cross-border finance. As shown in a new report that I co-authored with Katherine Soverel (of Boston University), Chilean economist Ricardo French-Davis and Malaysian economist Mah-Hui Lim, TPP countries such as Chile and Malaysia - one in the Americas, the other in Asia - regulated cross-border finance in the 1990s to prevent and mitigate severe financial crises.

Their experience proved critical after the 2008 global financial crisis, when a global rethink started to find the extent to which cross-border financial flows should be regulated. Many countries, including Brazil and the Republic of Korea, have built on the example of Chile and Malaysia and re-regulated cross-border finance through instruments such as tax on short-term debts and foreign exchange derivative regulations.

It is only prudent that, after the global financial crisis, emerging market economies want to avail of as many tools as possible to protect themselves from future crises. And new research in economic theory justifies this.

Economists at Peterson Institute for International Economics and Johns Hopkins University have demonstrated how cross-border financial flows generate problems because investors and borrowers do not know (or ignore) the effects their financial decisions have on the financial stability of a given country.

In particular, foreign investors may well push a country into financial difficulties - and even a crisis. Given that constant source of risk, regulating cross-border finance can correct this market failure and also make markets function more efficiently.

This is a key reason why the IMF changed its position on the crucial issue of capital flows; it now recognizes that capital flows create risks - particularly waves of capital inflows followed by sudden stops -which can cause devastating financial instability. To avoid such instability, the IMF now recommends the use of cross-border financial regulations.