Decoding the Middle-Income Trap

- By Danny Quah

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, July 20, 2013

E-mail China.org.cn, July 20, 2013

The spectre of the Middle-Income Trap stalks China and the rest of the world's successful emerging economies. The Trap dictates that no matter how rapidly they initially grow, all emerging economies will eventually slow.

The proposition that fast-growing economies will eventually slow is called "neoclassical convergence" – when capital-deepening has run its course and any further advance in prosperity can come only from technological progress, whether through indigenous innovation or through importing techniques from any economies which are still rapidly growing.

But neoclassical convergence is an old idea. Moreover, it predicts that slowdown occurs when emerging economies smoothly and gradually catch up with, and achieve equality with, advanced ones. In contrast the newer hypothesis of the Middle-Income Trap puts forward two further claims: First, that the slowdown occurs with a bang, not a whimper; and second, that the economy in question slows long before it achieves parity with rich countries.

Certain evidence is obviously unhelpful when studying the Middle-Income Trap. Take the example of a sudden economic slowdown in a rich country. It matters hugely for economic policy in that country whether that slowdown has occurred because its labour markets have grown sclerotic, or its financial markets have seized up, or the entire economy has become uncompetitive in a globalized world. But such a slowdown is irrelevant as evidence of the Middle-Income Trap.

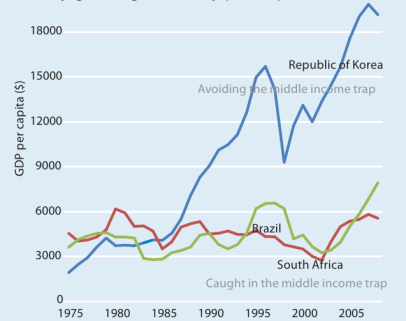

Instead, the evidence which gives the greatest insight into the Middle-Income Trap is revealed when reality throws out examples of who has been trapped and who hasn't. Otherwise, the Middle-Income Trap is just a trawl – like illegal fishing for sushi which indiscriminately nets both tuna and dolphin.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) provides a dramatic graphic on this:

|

|

Asia Development Bank, 2011: Realizing the Asian Century. |