Behind China's liquidity crisis

- By John Ross

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, July 2, 2013

E-mail China.org.cn, July 2, 2013

In June, China suffered its worst liquidity crisis in over a decade. Fortunately, the Central Bank reversed the situation by extending liquidity operations to responsible financial institutions.

|

|

|

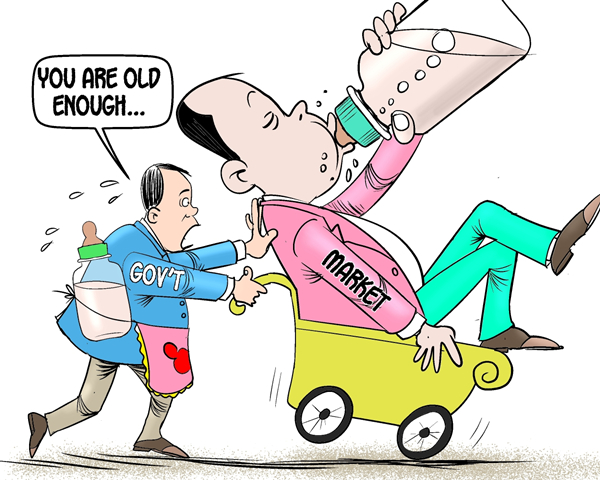

Time to let go[By Jiao Haiyang/China.org.cn] |

In the West, some sections of the media exploded with wild comparisons to the US financial crisis in 2008. Such comparisons were nonsense, however, based on an elementary economic mistake. The U.S. did not suffer a liquidity crisis in 2008. It faced an insolvency crisis. The former is a shortage of means to meet immediate payments; the latter occurs when banks' liabilities exceed their capital. In 2013, Chinese financial institutions faced liquidity problems, but not a single major institution failed. Numerous U.S. financial institutions collapsed in 2008. Comparing the two events is rather like claiming that the flu and the bubonic plague are equally serious, since both are illnesses!

But not being the bubonic plague doesn't mean that in its own terms flu is not unpleasant, or that it doesn't have side effects that last for some time. Therefore, it is important to analyze the crisis' causes in order to determine whether similar events will recur. While the exact form of crisis was not predictable - it never is - both Chinese economists and the present author predicted why there would be problems for the Chinese economy. Now that June's symptoms have been somewhat ameliorated, whether a similar crisis emerges in the future depends on whether the key mistake that led to the present one is resolved.

The key symptom of June's crisis was a spike in interbank lending rates to a 13 percent peak. Willingness to pay this indicated that financial institutions urgently needed cash. Analyzing the links between the underlying disease and the symptoms shows why.

The core problem that led to the liquidity crisis was advocacy that China abandon the policies which for 35 years have made it the world's most rapidly growing economy, in favor of something termed"consumer led growth," a theory that boosting consumer demand will lead companies to a more rapid increase in production of consumer goods and a more rapid rise in living standards. Unfortunately, this theory factually doesn't take into account that investment is the main source of economic growth, and conceptually it doesn't understand what a market economy actually is.

A market economy necessarily can only be "profit led growth." Output does not increase due to "demand," but only because of profit. Failure to understand this pushed the economy towards the liquidity crisis via its key policy proposal that the percentage of consumption in China's GDP be increased, and to pay for these purchases the percentage of wages in GDP should increase.

Increasing the percentage of wages in the GDP necessarily means reducing the percentage of profits. Therefore the theory of "consumer led growth" in reality advocated that a profits squeeze should be applied to companies via wages growing more rapidly than GDP. Regrettably, in the first part of 2013, this policy was pursued, with China's consumption rising significantly more rapidly than its investment, an indication wages were rising more rapidly than GDP. This produced the only possible consequence in a market economy: a chain reaction leading to crisis, which duly broke out in June in credit markets.