Prospects and the city

- By John Ross

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, May 30, 2013

E-mail China.org.cn, May 30, 2013

China’s economic policy rightly identifies urbanization as a key strategic aspect which unifies both long and shorter term goals. From a longer term perspective, all advanced economies are urban; from a shorter term viewpoint, city incomes in China are three times rural ones, reflecting the higher productivity of urban employment. Urbanization therefore allows China to create an immediate increase in productivity and living standards. Estimates by the China Development Research Foundation that the country’s urban population can increase from its current 50 percent to approximately 70 percent by 2020 are central to achieving China’s goal of doubling GDP in the same period.

But not all of the implications regarding urbanization have been thought through yet, as indicated by the fact that a comprehensive plan for meeting urbanization’s costs has yet to be published.

This key interrelation between the financial and physical aspects of city development is something I am acquainted with. During my eight years in charge of London’s business policy, drawing up economic perspectives for city development was one of my chief responsibilities. As Senior Fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China, discussions with China’s urbanization experts have confirmed that the key principles of city development necessarily apply in both the initial stages of urbanization and during its development.

The fundamental principle of successful urban progress is that physical development must flow from and logically express the underlying economic, social and environmental dynamic and this applies both to the initial stages of urbanization and further city development. As China aims to create advanced cities, and London has the highest productivity of any major urban center outside the U.S., it was fascinating to discover in discussion with Chinese experts how this principle applies at every stage.

The first key issue is, therefore, making a correct estimate of which type of city economy will be dominant in China during the next stage of urbanization, which will occur over the next 10-20 years. Naturally there will be variety between different Chinese cities. But this does not alter the reality that, taking into account China’s overall level of development, one city type, the industrial based one, will be dominant in the urbanization process. Lack of clarity on this would necessarily lead to mistakes in urbanization just as in more narrowly defined economic policy.

An example can illustrate this. A city’s transport system is simultaneously one of its most expensive pieces of infrastructure, therefore crucial for its finances, and critical for its inhabitants. Severe traffic problems in cities such as Beijing create significant economic losses and lower the quality of life.

But the transport requirements of industrial and service-based cities differ substantially. Industrial or factory-based development is generally best not located in city centers for both environmental and economic reasons – it is polluting and land prices are usually highest in city centers. Transporting industrial products through city centers is impractical and undesirable. Therefore huge parts of the transport system of industrial-based cities are oriented towards its outskirts – getting large numbers of people to work away from the city center and transporting goods from city peripheries.

Service-based cities are different. International experience shows that huge benefits derive from clustering services such as finance and creative sectors in, or close to, city centers. Service-based cities’ transport systems must therefore be constructed to allow them to take huge numbers of workers to the city center. New York, with its super-dense Manhattan skyline, and London with its extreme concentration of financial services in the Square Mile and clusters of creative industries around it, are the extreme examples of this.

Environmental choices are equally linked to the type of city development that will occur in China. For example, I recently attended a seminar held to analyze tackling the recent instances of smog in Beijing in which the model advocated was one which copies U.S. environmental approaches. This is both wrong in concept and impractical. The background to U.S. and U.K. approaches to city environmental problems was deindustrialization, with its rapid shrinkage in relative or absolute terms of industry and the pollution it causes.

This approach is entirely impractical in China. For the next 10-20 years, China’s economy will remain centered on industry, although a shift from medium to high technology production will take place. The key city examples for China to study are, therefore, in countries which combine advanced industrial production with successful environmental protection. Germany and Japan are the most advanced examples of this.

That China’s urbanization will be dominated by industrial based cities is determined by the fundamental facts of its economic development. In 2012, China’s GDP per capita was slightly over $6,000. The goal is to double the 2010 GDP per capita figure by 2020, taking China close to the slightly above $12,000 a year per capita GDP, which the World Bank defines as the threshold for a “high income” economy.

Let us though, make a comparison with South Korea. This is a country still dominated by industry which has not yet made the transition to the more advanced stage of a service-based economy. South Korea’s 2012 per capita GDP was slightly above $23,000 – almost four times China’s current level of development. Even at current growth speeds it will take China 20 years to reach South Korea’s average level of development. It is certain, therefore, that China’s next phase of urbanization will be based on the construction of industrial cities, as it is too early in China’ development to undergo a widespread transition to service-based cities. Consequently, creating high quality industrial-based cities is the key issue in China’s urbanization.

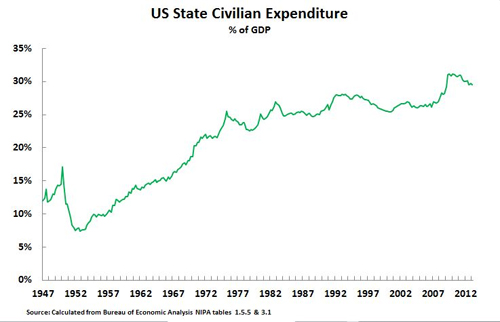

Finally, this interrelates with finance. City development requires gigantic investment, trillions of dollars, in housing, transport, power supply, sewerage, information technology infrastructure, environmental protection and numerous other fields. In some circles in China there is an illusion that as the country’s economy develops, and urbanization proceeds, the economic role played by, and the expenditure of, the state will decrease in importance. This is simply false – as the chart which shows the percentage of GDP accounted for by state expenditure in the U.S. shows. All factual evidence demonstrates that as an economy develops and urbanizes the role of the state, the percentage of expenditure accounted for by the state will increase.

|

|

Urbanization will, therefore, dramatically transform the lives of China’s citizens. But it will also transform its economic and financial structure.

The author is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit:

http://www.formacion-profesional-a-distancia.com/opinion/johnross.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn

Add your comments...

Add your comments...