Global banks pulling back from overseas business

- By Howard Davies

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail Shanghai Daily, May 25, 2012

E-mail Shanghai Daily, May 25, 2012

Global policymakers regularly congratulate themselves on having avoided the errors of the 1930s during the financial crisis that began in 2008.

|

|

|

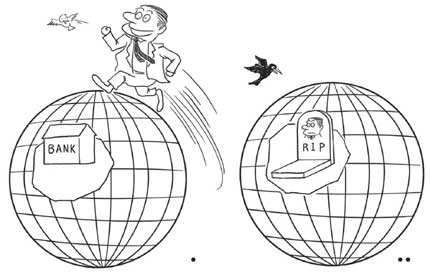

[By Zhou Tao/Shanghai Daily] |

Led by US Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke, an economic historian of the Great Depression, they remembered the ideas of John Maynard Keynes and loosened monetary and fiscal policy to avoid the worst. We are still coping with the budgetary consequences, especially in Europe, but it is true that the world did not end in 2008.

Monetary tightening was not the only major policy error of the 1930s; so was a retreat into protectionism, symbolized by the Smoot-Hawley tariff increases at the beginning of that decade. Historians continue to debate the centrality of the Smoot-Hawley law itself, but the subsequent tariff war certainly damaged trade and economic growth, making a bad situation worse.

Today's statesmen like to say that they have avoided the protectionist error as well, but is that true? Certainly I do not expect a tariff war to break out in the near term, but there are dangerous indicators of trade trouble ahead.

The Doha round of global free-trade talks has been abandoned, and the World Trade Organization is now languishing by the lake in Geneva, uncertain of its future. Perhaps Doha was unlikely to achieve much in the current circumstances, but the absence of any continuing dialogue on world trade - at worst, a useful safety valve - adds a new level of risk. While people are talking, they are less likely to act precipitately.

In the financial arena, there're many signs of a revival of nationalistic approaches to regulation and currency policy. The crisis challenged the Washington Consensus, which assumed that the world was moving towards free movement of capital and market-determined exchange rates. Several countries have now imposed capital controls of various kinds. Even the International Monetary Fund, long the embodiment of the Washington Consensus, has acknowledged that "capital controls are a legitimate part of the toolkit to manage capital flows in certain circumstances."

Deglobalization

These early signs of deglobalization of financial markets have their parallels in commercial banking, with some of the biggest global institutions retrenching rapidly. Citibank and HSBC had gone further than most in developing a global footprint; indeed, one can hardly get on a plane nowadays without being reminded that the latter is "the world's local bank." But both are closing down in many countries.

Likewise, many other European banks are cutting back their overseas business sharply. The impact is particularly vivid in trade finance, where European banks have been major participants in Asia. Now they are in rapid retreat from that market, creating a worrying gap that Asian banks are seeking to fill.

There is more to come. As they struggle to raise new capital, European banks and insurers are likely to be forced to sell overseas assets.

If this were simply a sign of a new, tighter focus on viable long-term strategies, it might be regarded as a benign development. But there are indications that the process is being driven by regulatory change, and in some cases by regulatory protectionism.

Banks are overseen by a "home" regulator in their country of incorporation, and by a series of "host" regulators where they operate. "Home" regulators and lenders of last resort are increasingly worried about their potential exposure to losses in banks' overseas operations. As Mervyn King, the Governor of the Bank of England, acutely observed, "banks are global in life, but national in death." In other words, home authorities are left to pick up the tab when things go wrong.

Host regulators are increasingly nervous about banks that operate in their jurisdictions through branches of their corporate parent, without local capital or a local board of directors. So they are insisting on subsidiarization. From the banks' perspective, that means that capital is trapped in subsidiaries, and cannot be optimally used across its network. So banks may prefer to pull out instead.

A particular version of this phenomenon is at work in the European Union. In the single financial market, banks are allowed to take deposits anywhere, without local approval, if they are authorized to do so in one European country. Yet when the Icelandic banks failed, the British and Dutch authorities had to bail out local depositors. Now regulators are discouraging such cross-border business, leading to a process with the ugly new name of "de-euroization." We can only hope that it does not catch on.

Regulators, recognizing the risks of allowing financial deglobalization to accelerate, have been seeking better means of handling the failure of huge global banks. If banks can be wound up easily when things go wrong, with losses equitably distributed, regulators can more easily allow them to continue to operate globally and efficiently.

Uphill work

So a major effort to construct a cross-border resolution framework is under way. But it is uphill work, and Daniel Tarullo, a governor of the Federal Reserve, has acknowledged that "a clean and comprehensive solution is not in sight."

Does all of this amount to a serious threat to the benefits of globalization? The cautious answer would be that it is too early to say. Perhaps we are just seeing the beginnings of a changing of the guard, and that HSBC and Citibank will be replaced as global players by China's ICBC, Brazil's Itau Unibanco, or Russia's Sberbank.

But it may be that we are seeing a revival of a less benign Keynesian doctrine: "ideas, knowledge, science....should of their nature be international. But let goods be homespun wherever it is reasonably and conveniently possible and, above all, let finance be national."

Howard Davies, a former chairman of Britain's Financial Services Authority, deputy governor of the Bank of England, and director of the London School of Economics, is a professor at Sciences Po in Paris. Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2012.www.project-syndicate.org