Eight years ago at an excavation site in Tianjin a dozen archaeologists studied an unearthed iron piece but could not identify the strangely shaped metal.

Then a young voice chipped in: "It is an iron coin cast by the Baofu Foundry in Fujian province, during the reign of Emperor Xianfeng (1850-61) during the Qing Dynasty."

|

|

|

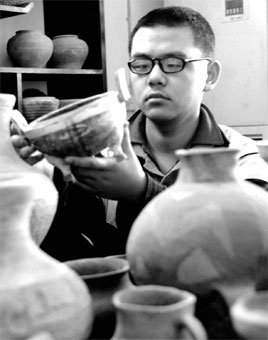

Hao Di has been collecting antiques since he was 5. |

As those present turned to the speaker, in shock, he went on: "Roughly made, the coins were not put in circulation but used to make cannons."

"People used copper at that time. There were no iron coins," one archaeologist said dismissively.

"You may find shells if you dig deeper," the boy, who wore an antique pair of black-framed glasses said.

No one took him seriously until, minutes later, an iron shell measuring 4 cm in diameter was dug up.

The boy was Hao Di, a 15-year-old archaeology prodigy. The Tianjin native has been collecting rare ancient coins, armor and bronze swords since he was 5 years old.

He rose to fame in archaeology and collection circles at the age of 12 for discovering a set of three Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) coins and an ancient bronze sword.

Now the 23-year-old Hao provides advice to museums here and abroad, and at archaeological excavations. He is also the youngest guest professor with the department of history, at Peking University.

Hao's interest in archaeology was a surprise to his parents.

"Hao Di was silent in childhood. He seldom talked to or played with other kids. He seemed to be interested in nothing, not even toys," says father Hao Wenmin.

He recalls taking 5-year-old Hao to a grocery market. The boy was fascinated by a street stall selling ancient coins and didn't want to leave. His father returned home, forgetting his child momentarily, and on his return found Hao Di had categorized the coins into two groups and strung them with his shoelaces.

"On that day, Hao Di formed his first collection," says his father. "Though we didn't realize that he would be so much into it in the future."

A year later Hao Di had become a frequent dealer at a famous antique market in Tianjin. He once carried home four bags of broken ceramic pieces excavated at a construction location. He sold them at the market and earned 170,000 yuan ($24,900).

His purchases included a coin from the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace (Taiping Tianguo, 1851-64) period, which he bought for 5 yuan. It is the only one of its kind and may be worth up to 40,000 yuan ($5,900) now.

Wang Peng, a writer and collector and Hao's neighbor, introduced a friend to Hao Di one day.

"My friend is a celebrated coin collector. He showed Hao Di his collection of more than 3,000 ancient coins, to which he had added seven replicas, on purpose. Hao looked over them for three minutes and stunned my friend by correctly spotting all the fake ones," he says.

Hao Di believes he has a kind of spiritual power to distinguish antiques from counterfeits.

An ideal day for him is spending time going through his treasure trove of antiques, which includes about 200,000 coins, 3,000 ancient weapons, 7,800 bronze mirrors and dozens of sets of armor. He also spends a lot of time in libraries studying the Chinese classics and archaeology books.

"There are stories behind each of the items in my collections that would take a whole lifetime to explore," Hao Di says.

Despite being dubbed an archaeological genius, Hao Di's father did not appreciate this for many years.

"I didn't understand why he was so crazy about antiques. I didn't know why he collected and studied them. I wanted him to quit and devote himself to schooling wholeheartedly. We didn't get along with each other," Hao Wenmin says.

Hao Di lost his grandfather when he was 9. He felt enormously sad and guilty about his grandpa passing away.

"He told me after the funeral that grandpa had given almost all the money for his medical treatment to him in order to buy a rare bronze sword. My father was his financial backbone for a long time, though he lived on a small pension himself," Hao Wenmin says.

A few months before Hao Di graduated from primary school, he was diagnosed as suffering from malnutrition and anemia.

"We gave him 15 yuan a day for breakfast and lunch. But he saved all the money to buy antiques. I felt so guilty that I held him tightly all the way back home (from the doctor). Finally, we made up," Hao Wenmin says.

Since then, he has been totally supportive of Hao Di. They are usually together when Hao Di does an archaeological excavation.

"He often works in desolate ancient battlefields for days. He doesn't eat much and suffers a lot. He has won wide recognition for his professionalism and dedication. I feel so proud of him and his job," Hao Wenmin says.

Hao Di is sometimes called "Golden Eyes" as he is in demand across the country to evaluate antiques.

On one occasion, a couple of poorly dressed unemployed laborers brought a load of antique heirlooms to him. They needed 100,000 yuan ($14,700) to pay for their children's college tuitions. The highest quotation they had obtained was 50,000 yuan ($7,400).

Hao said one item was worth about 350,000 yuan ($51,500) and then divided the antiques into three piles, saying the other two piles were worth 50,000 yuan each.

He gave the pair phone numbers of three possible buyers, saying: "Just tell them I have seen your stuff."

He didn't charge them for the appraisal. He only charges antique collectors and dealers.

"Your collections will fill up four medium-size museums," a Japanese Sinologist said after a brief tour of Hao Di's immense treasure trove. He reportedly offered 100 million yuan ($14.7 million) for the collections but was declined.

"Much of my collection will not sell well on the market. But if I don't keep these things, our descendants may not have real antiques to appreciate and study," Hao Di says.

He is now writing a book about ancient Chinese coins and seeks to popularize collecting antiques.

(China Daily February 3, 2009)