Production of fireworks sparks safety concerns

Industry remains plagued by accidents despite greater use of technology.

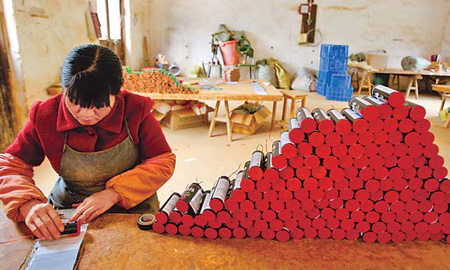

Wen Yuehui's hands were like pistons as she fitted fuses into bunch after bunch of firecrackers. On a freezing Sunday afternoon in a small building with no doors, the furious repetition was the only thing keeping her warm.

|

|

|

A worker assembles fireworks at a workshop in Liuyang, Hunan province, in this file photo taken on Dec 10, 2010. |

The 50-year-old has been making fireworks to earn extra cash for decades; only now instead of working alone in her home, she toils alongside dozens of others at Feilong Firecracker Factory in Yizhang county, Hunan province.

Government safety crackdowns throughout the county have all but wiped out the once-ubiquitous family workshops, forcing 40,000 farmers to find post-harvest jobs with registered and, more importantly, regulated businesses.

The result has been a sharp drop in the number of fireworks-related deaths. Official data shows that 188 people were killed in explosions in 2009, compared to the annual average of 400 between 1986 and 2005.

China is already the world's largest producer, consumer and exporter of fireworks, with a total output in 2010 topping 28 billion yuan ($4.2 billion). Yet, with the industry growing at 10 to 15 percent a year, experts warn that technology now being used by factories nationwide to increase productivity and reduce the reliance on manual workers is potentially creating new dangers.

On Nov 15 last year, one person was killed and two injured when a machine being used without the proper safety certificates exploded at a plant in Baitutan town, Liling city, also in Hunan. Two more died in a similar accident several weeks later in nearby Pukou town.

Wen earns 90 jiao ($0.13) for every 800 fuses she fits and, at peak times like the run-up to the Lunar New Year, can earn about 800 yuan a month. For decades, workers like her have been the backbone of the industry. However, as more young people migrate to cities for better salaries, fireworks manufacturers are investing in technology to protect their profits in the face of labor shortages.

Feilong recently spent 540,000 yuan to install six machines that automatically knit firecrackers. Running at full speed, each one can do the work of six or seven people.

Such technology is making production quicker, but not necessarily safer, according to Li Guoyu, a senior engineer with Yizhang county's work safety administration. He warned that some factories are even modifying machines to run faster. "That's far more dangerous than making firecrackers by hand".

In Liuyang, another major fireworks production base in Hunan, the labor shortage is even more acute. The industry there needs more than 300,000 workers, yet recruitment is proving difficult.

"We went to Sichuan (province in Southwest China) with the idea of hiring more than 4,000 migrant workers for our factories. In the end, we got only 1,600," said Hu Jianjun, deputy director of the city's fireworks and firecrackers administration bureau. "Those who did come, many of them didn't want to stay in Liuyang for long.

"The fireworks industry has always relied heavily on human labor, and mechanized production is growing at a very slow pace," he said, adding that some large companies are working with engineers to develop new technologies.

Working toward safety

One major hazard is the fact many machines on the market have no safety certification.

At Yongxing Gaoting Gaotang, a small firecracker factory beside a graveyard in a county neighboring Yizhang, boss Li Wushan visibly jumped when asked if the area had suffered any explosions. "We don't talk about that here. It's a bad omen," he said.

Yet, when it came to the topic of his machines passing quality tests, he added: "Even machines used in larger factories don't have safety certificates."

Despite the dangers, Zhao Jiayu, a professor of pyrotechnics chemistry at the Beijing Institute of Technology, said he believes the development of new technology is a key to modernizing this traditional industry and decreasing the number of casualties.

The industry will only be safe "when workers are operating machines from another room with a switch", said Zhao, who is also a member of the National Standardization Technology Committee of Fireworks and Firecrackers. "That way, the damage caused by an explosion is limited."

Under the central government's 11th Five-Year Plan (2006-2010), researchers also received State funds to explore safer fireworks knitting machines and explosives.

Compared to the outlawed home workshops, experts agree that registered factories are safer working environments for villagers. However, there is still a long way to go before the industry is "accident-free", said Yang Zhen, secretary of the politics and law committee in Yizhang's Yanquan town, the official in charge of production safety.

"Every time my cell phone rings after 10pm, I know there must be something wrong," he said, adding that daily checks are carried out to ensure businesses are not neglecting safety for profit.

He recalled that, before the crackdown on family-run workshops, it was common to find villagers' homes littered with fuses and half-finished firecrackers. "One villager's workshop was right next to his kitchen," he said.

Today, the vast majority works in larger, registered factories, which are required to meet certain safety standards. However, the industry also needs good management and training to reduce incidents of malpractice.

Bad management, according to data from the State Administration of Work Safety, causes more than 80 percent of work-related accidents, including those at fireworks factories.

In August last year, 33 people were killed in a blast at a plant in Northeast China's Heilongjiang province. Authorities discovered the company was attempting to produce large aerial fireworks instead of the firecrackers it was approved to make.

On Nov 24, an explosion destroyed three buildings at Fuguishan Fireworks Factory in Chengde, Hebei province, killing six people and injuring 10 others. Three days later in Zhoukou, Henan province, six more died when eight buildings collapsed at Dawuzhuang Fireworks Factory. Separate investigations proved both incidents were due to overloading explosives and poor storage practices.

Safety regulations state that workers inserting fuses can store a maximum of only six packs of loaded firecrackers in the room with them. Once finished, the packs must be transferred to another room. Many factories have large signs on walls that remind employees to transfer the products frequently and safely. Yet the rule is often ignored.

"Workers will pile more packs in the room to save walking time," said engineer and safety expert Li Guoyu as he watched workers at Feilong carry packs of firecrackers. "Just 40 packs of half-finished firecrackers are enough to destroy an entire building."

Town safety official Yang also revealed that some businesses are still outsourcing work to family workshops.

"It's cold in winter, and if one villager uses a heater while making firecrackers it could be an unimaginable disaster," he said, adding that his job not only involves inspecting 39 firecracker factories, but also searching for illegal workshops that open during peak times. "People who make firecrackers at home still make a bit more money than those working for factories," he said.

Battling against illegal workshops is not easy when fireworks are a village's pillar industry. Ma Deqing, Party secretary for Shanfeng village in southern Hunan, was killed in 2003 when the firecracker workshop on the second floor of his house exploded. He had started the business to provide jobs for his neighbors.

Yang said he even closed down an illegal firecracker factory opened by his brother. "He was so angry that he dragged me into the room full of firecrackers and said he wanted to die with me," he recalled.

Although the industry does not generate much tax revenue for the Yanquan government, it does benefit villagers by creating employment opportunities, which in turn helps to ensure a lower crime rate, added Yang.

0

0